| Artists showing works at ramfoundation |

| Erik Odijk (NLD) |

Lange lijnen in de tijd Mark Kremer (2010)

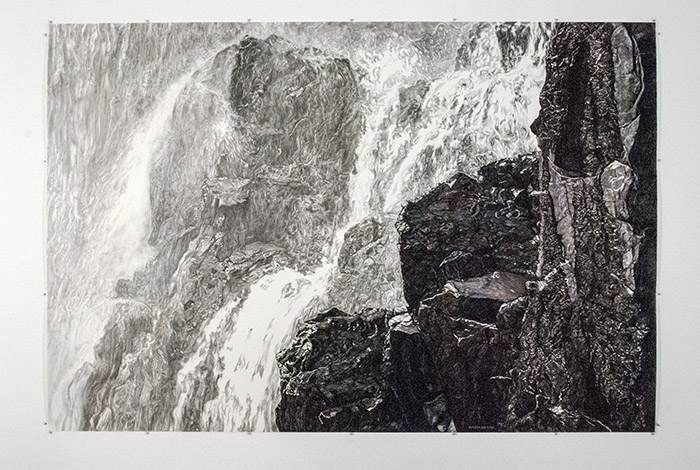

Praktijk Erik Odijk maakt tekeningen in zijn atelier en op expositieplekken waar hij in situ op de wand werkt. Protagonist in zijn oeuvre is de natuur, de kunstenaar trekt door wilde landschappen en grijpt in zijn werk terug op de ervaring van de plek. Zijn getekende landschappen zijn lieflijk en woest. Een gelaagde tekenstijl maakt het spinsel van de tijd en haar langzame greep op de natuur voelbaar. De stijl is traditioneel; in formeel opzicht doet ze denken aan de hallucinante lijnvoering in de landschappen van Jan Toorop uit de periode van het Symbolisme. Erik Odijk verbeeldt de levenskracht en duisternis van de natuur. Zijn werk is doordrongen van de idee dat het werkelijk ondergaan van de natuur een roeservaring is waar we in onze tijd moeilijk toegang toe hebben. Om deze reden krijgt de fotografie in zijn huidige werk een belangrijker plaats. Recentelijk stelt Erik Odijk fotoreeksen samen van zijn tochten door landschappen, en hiermee wordt er een objectieve blik op de ervaring van de plek in het spel gebracht. De foto's vormen een contrapunt voor de tekeningen, en zijn een uitbreiding van het onderzoek naar de natuurervaring in de 21ste eeuw.

Situering Het oeuvre van Erik Odijk (*1959) wortelt in de jaren tachtig. In die tijd ontstonden originele plastische oeuvres, deels als reactie op de iconoclastische reflex van de conceptuele kunst. In Erik Odijks werk vind je ook een conceptuele ascese terug maar die wordt gecombineerd met haar tegenhanger: formele exuberantie (denk aan de Barok en het al genoemde Symbolisme). Zo wil de kunstenaar traditie en moderniteit bij elkaar brengen. Voor zijn vroege werk, en de ontwikkeling van een beeldtaal, kijkt Erik Odijk naar de traditie. Hij is een kunstenaar van de jaren tachtig, omdat hij weer lange lijnen in de tijd wil trekken (net als de kunstenaars van de neo-stijlen). In de Nederlandse context deelt hij die interesse met generatiegenoten als Jan van de Pavert, Fortuyn/O’Brien en Harmen Brethouwer, die elk op een eigen manier inzoomen op aspecten van de moderne cultuur en haar geschiedenis. De natuur en de natuurervaring vormt voor Erik Odijk een lens om het kruispunt van traditie en moderniteit in beeld te brengen. In zijn eigen kunstenaarsteksten schrijft hij hier expliciet over, zoals wanneer hij verwoordt wat er gebeurt als hij de wildernis opzoekt in natuurreservaten waar natuur een decor is geworden.

Positie Erik Odijk neemt een romantische kunstenaarspositie in. In deze context noemt hij Richard Long als een belangrijk kunstenaar. Zijn eigen oeuvre is een afspiegeling van de individuele (natuur)ervaring en wil daarmee samenvallen, maar het is tegelijk doordrenkt van een besef van onmogelijkheid, van de radicale grens die een intense ervaring scheidt van de overdracht. Het opzoeken van de natuur, het verlangen om met de natuur te versmelten, gaat terug op de Romantiek. In de periode van de Romantiek ontstaat een nieuw paradigma waarin consensus op basis van denken vervangen wordt door verschil -en acceptatie ervan- op basis van gevoel. Maar de ontdekking van een individuele gevoelswereld door dichters, denkers en kunstenaars had een sterk reflectieve component. Men raakte gefascineerd door de wereld van het gevoel: een zone waarin de mens, niet meer gekluisterd door ratio, bevrijding zou beleven. Maar men besefte terdege dat de mens in die wereld langs zijn eigen afgrond scheert, zoals geïllustreerd door Lenz, de novelle van Georg Buchner uit 1832, waar het hoofdpersonage aan zijn gevoel i.e. natuur is overgeleverd en die blijkt onontkoombaar en fataal. Lenz leest als waarschuwing: net als in de Romantiek omarmen kunstenaars van nu de romantische gedachte maar houden haar tegelijk op afstand. Zo weet Erik Odijk op zijn tochten door de natuur waar het ravijn is, omdat er een reling voor staat. Zijn oeuvre werpt de vraag op hoe het tegenwoordig zit met de romantiek van de natuur en het maakt duidelijk dat we er nog steeds niet goed zonder kunnen.

Statement Het oeuvre van Erik Odijk is belangrijk door de pregnante verbeelding van een van de grote onderwerpen van onze tijd: de veranderende perceptie van de natuur. In zijn werk betrapt hij het gespleten gevoel van de natuurreiziger, die weet dat elke stap die hij zet mogelijk schade toebrengt aan deze omgeving maar die niettemin de roep van de wildernis niet kan weerstaan. De innerlijke tegenstrijdigheid die deze kunstenaar/reiziger ervaart, komt op een overtuigende manier naar voren in zijn teksten over de huidige roep om natuur in onze cultuur. “Arcadische dualiteit is een thema waarin ik me verdiep. De twee soorten Arcadië: ruig en lieflijk, donker en licht... Het pastorale Arcadië van de goede smaak, harmonie en aangepaste vormen tegenover het woeste, ruige en verontrustende Arcadië zoals een wildernis.

|

Long Lines Through Time Mark Kremer (2010)

Practice Erik Odijk makes drawings in his studio and in situ at exhibitions where he draws on the wall. Nature is the protagonist in his oeuvre. The artist roams through untamed landscapes and recapitulates the experience of place in his work. His drawn landscapes have a rugged charm. The multilayered graphic style makes tangible the tendrils of time and their slow entwining of nature. The style is a traditional one; in formal respects, it recalls the hallucinating quality of line in the landscapes of Jan Toorop in his Symbolist period. Erik Odijk depicts the vitality and the darkness of nature. His work is suffused with the idea that the real experience of nature is a euphoric one which is denied to us by our civilized lifestyle. This is why photography is gaining a more prominent role in his present work. Erik Odijk has recently been compiling photographic series relating to his landscape walks. These add an objective angle on the place experience : the photographs are a counterpoint to the drawings, and so expand his study of the experience of nature in the 21st century.

Context The oeuvre of Erik Odijk (b. 1959) has its roots in the 1980s. It was a time of original, plastic oeuvres that arose partly in reaction to the iconoclastic reflex of Conceptualism. In Erik Odijk’s work we may also recognize a certain conceptual asceticism, but it is combined with its opposite – a formal, almost Baroque or Symbolist, exuberance. It discloses a wish to combine tradition and modernity. In his early work, as he was developing a visual idiom, Erik Odijk is a traditionalist. He is a typical artist of the Eighties in that he endeavours to establish long, connecting lines through time (in the same way as adherents of the Neo-styles). In the Dutch context, he shares this interest with such contemporaries Jan van de Pavert, Fortuyn/O’Brien and Harmen Brethouwer, each of whom focuses in a distinct way on aspects of modern culture and its forebears. Nature and the experience of nature give Erik Odijk a lens to zoom in onto the intersection of tradition with modernity. He makes this explicit in his artist’s texts, for example by describing what happens when he seeks the wilderness in nature reserves where nature has become little more than a backdrop.

Positioning Erik Odijk’s artistic stance is a Romantic one. He cites Richard Long as an important artistic reference. His own oeuvre is a reflection of the individual experience, especially of nature, and attempts to reproduce it. Yet it is saturated with awareness of the impossibility of doing so, of the radical boundary that separates an intense experience from the act of communicating it. Retreating into nature, and the longing to become one with it, are hallmarks of classic Romanticism. The Romantic era saw the rise of a new paradigm in which a consensus based on rational thought was usurped by the idea of difference, and the acceptance of difference, based on personal sensation. But the discovery of an individual sensual and emotional world by poets, philosophers and artists, had a strongly reflective component. People were fascinated by the realm of sensation, a zone where, unencumbered by ratio, one might experience freedom. At the same time they were well aware that, in that world, the individual moved ever closer to his own personal precipice; as was illustrated by the character Lenz in the 1832 novella by Georg Büchner, who, submitting totally to his emotions (and hence nature) finds them irresistible yet eventually fatal. Lenz is a warning to us. As in the Romantic era, artists of today embrace the notion of the Romantic but preserve a little distance from it. In his nature walks, Erik Odijk knows where the precipice lies, because it has a safety railing. His oeuvre raises the question of the part played by the romanticism of nature, and makes it clear why even today we cannot manage without it.

Statement The oeuvre of Erik Odijk is important because of its trenchant portrayal of one of today’s great issues: our changing perception of nature. His work catches us out with the divided feelings of the nature explorer, who cannot resist the call of the wilderness yet knows that every step taken could add to its destruction. The inner conflicts felt by this artist/explorer emerge with conviction in Erik Odijk’s writings when he refers the appeals to nature that appear so frequently in our culture. “Arcadian duality is a theme that concerns me deeply. There are two kinds of Arcadia – raw or gentle, dark or light; the pastoral Arcadia of good taste, harmony and moderate form, as against the untamed, coarse, alarming Arcadia of the wilderness. |

| latest news |

| 25-05-2025 |

|

| Kunstenaars elders / Artists elsewhere |

| latest interview: |

| 03-09-2024 |

.jpg) |

| Linda Selena Boos interviewt Fatima Barznge en Martijn Simons |

| latest article: |

| 31-03-2025 |

|

| Judith Kuipéri : Art Rotterdam 2025 – impressies |

| contact |

| stuur ons een e-mail |

| Secretariaat |

| Lloydkade 627 3024 WX Rotterdam |

| Open: |

| alleen op afspraak |

| only by appointment |